|

en français

|

time schedule

| feature films |

short films

|

program

[PDF]

2007

Festival Feature Films (March 30 - April 1)

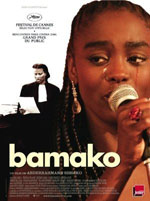

Director Abderrahmane Sissako presents this special screening of Bamako

director Abderrahmane Sissako screenwriter Abderrahmane Sissako producers Denis Freyd, Abderrahmane Sissako starring Aïssa Maïga, Tiécoura Traoré, Hélène Diarra running time 118 min

general audience

Description

Over the course of a few days, a trial pitting African civil society against the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund has set its stage inside the domestic courtyard of Chaka and Melé’s home in Bamako, the capital city of Mali. Judges have been  appointed, witnesses have been summoned and lawyers from both sides have arrived armed with passionate, scathing and uncompromising accusations. Is the World Bank guilty of not following its mandate to serve mankind or is Africa to blame for her suffering? Meanwhile, life in the courtyard presses forward. appointed, witnesses have been summoned and lawyers from both sides have arrived armed with passionate, scathing and uncompromising accusations. Is the World Bank guilty of not following its mandate to serve mankind or is Africa to blame for her suffering? Meanwhile, life in the courtyard presses forward.

Framed against the urgency of the trial, the case of a stolen gun leads a local detective to Chaka who lives in a home within the courtyard with his wife Melé. Melé is a popular bar singer, her husband Chaka is out of work and the couple is on the verge of breaking up …

In the midst of the powerful testimonials and pleas being made at the trial, the juxtaposition of Chaka and Melé’s story and those of their courtyard neighbors give a voice to Africa’s silent majority and further fortifies Africa’s case against the International institutions.

“A film that needs to be seen, argued over and seen again”

– A. O. Scott, The New York Times

“Very important, very impressive”

– Geoff Andrew, Time Out

Congratulations to Aïssa Maïga on her 2007 César nomination for Most Promising Actress. Congratulations to Aïssa Maïga on her 2007 César nomination for Most Promising Actress.

producer/director/screenwriter

Abderrahmane Sissako

| 2006 |

Bamako by Abderrahmane Sissako |

| |

Daratt (saison sèche) by Mahamat-Saleh Haroun |

| 2003 |

Malenkie lyudi (Les petites gens) by Nariman Turebayev |

| |

Le Silence de la forêt by Bassek Ba Kobhio and Didier Ouenangare |

| 2002 |

Heremakono (En attendant le bonheur) by Abderrahmane Sissako |

| |

Abouna by Mahamat-Saleh Haroun |

| 1998 |

La Vie sur terre by Abderrahmane Sissako |

| 1997 |

Rostov Luanda by Abderrahmane Sissako |

| |

Sabriya by Abderrahmane Sissako (short film) |

| 1996 |

Le Chameau et les bâtons flottants by Abderrahmane Sissako (short film) |

| 1993 |

Octobre by Abderrahmane Sissako (short film) |

| 1989 |

Le Jeu by Abderrahmane Sissako (short film) |

actress

Aïssa Maïga

| 2006 |

Bamako by Abderrahmane Sissako |

| 2005 |

Prête moi ta main by Eric Lartigau |

| |

Je vais bien, ne t’en fais pas by Philippe Lioret |

| |

Paris je t'aime – Segment: Place des Fêtes by Olivier Assayas |

| |

Caché by Michael Haneke |

| 2004 |

Les Poupées russes by Cédric Klapisch |

| |

Travaux, on sait quand ça commence… by Brigitte Roüan |

| |

L'Un reste, l'autre part by Claude Berri |

| 2003 |

Mes enfants ne sont pas comme les autres by Denis Dercourt |

| 2001 |

Les Baigneuses by Viviane Candas |

| 2000 |

Lise et André by Denis Dercourt |

| 1999 |

Jonas et Lila, à demain by Alain Tanner |

| 1997 |

La Revanche de Lucy by Janusz Mrosowski |

| 1996 |

Saraka Bo by Denis Amar |

actress

Maimouna Hélène Diarra

| 2006 |

Bamako by Abderrahmane Sissako |

| 2002 |

Moolaadé by Ousmane Sembene |

| 2000 |

Code inconnu, récit incomplet de plusieurs voyages by Michael Haneke |

| 1998 |

La Genèse by Cheick Oumar Sissoko |

| 1997 |

Taafé Fanga by Adama Drabo |

| 1996 |

Macadam Tribu by Zeka Laplaine |

| 1995 |

Guimba, un tyran une époque by Cheick Oumar Sissoko |

| 1989 |

Finzan by Cheick Oumar Sissoko |

Interview with Abderrahmane Sissako

First, this film is linked to my desire to shoot a film in [the] house of my father who has passed away. This house is located in Bamako, in the poorer neighborhood of Hamdallaye. It's a plain house, made of earth. For years, a tap and a well have been standing side by side in the courtyard. Here, water is expensive and to save money, my father dug a well.

This courtyard is where I grew up, with my many brothers, sisters, cousins, aunts, uncles, close and distant relatives. Never have we been less than 25 sleeping, eating, learning, living in turn, one after the other.

Today, most of us have left the house to live elsewhere – and yet the house is still always full. New cousins and close and distant relatives live there, go to school or quit to work on some odd job or another. For me, this house is associated with the memory of passionate discussions with my father about Africa.

The other reason that urged me to make this film has to do with my views on Africa. Africa is not the continent I call my own, but as a place of injustice which directly affects me. When one lives on a continent where filmmaking is difficult and uncommon, one feels entitled to speak in the name of others: faced with the seriousness of the situation in Africa, I felt a kind of urgency to bring up the hypocrisy of the north towards southern countries.

Director’s note

Today’s core missions of the Washington-based IMF and World Bank, which were created in the wake of World War II, are to regulate the international monetary system and lend money to developing countries. Since many countries had difficulty repaying their debts, rich countries imposed structural adjustment policies in the early ‘80s that set the rules of the game for millions of people. International financial institution officials were granted the power to impose a policy on the most debt-ridden countries’ governments that was supposed to balance their budgets. These days most sub-Saharan African countries are under structural adjustment programs. These programs based on neo-liberal principles serve rich countries’ vested interests, essentially those of the United States and of Europe. The reforms imposed on southern countries have always been the same while, paradoxically enough, they are far from being implemented in northern countries: suppression of state subsidies (in agriculture, textiles, etc.), the dismantlement of public services and job cuts in the public sector (school teachers, doctors, etc). Today’s core missions of the Washington-based IMF and World Bank, which were created in the wake of World War II, are to regulate the international monetary system and lend money to developing countries. Since many countries had difficulty repaying their debts, rich countries imposed structural adjustment policies in the early ‘80s that set the rules of the game for millions of people. International financial institution officials were granted the power to impose a policy on the most debt-ridden countries’ governments that was supposed to balance their budgets. These days most sub-Saharan African countries are under structural adjustment programs. These programs based on neo-liberal principles serve rich countries’ vested interests, essentially those of the United States and of Europe. The reforms imposed on southern countries have always been the same while, paradoxically enough, they are far from being implemented in northern countries: suppression of state subsidies (in agriculture, textiles, etc.), the dismantlement of public services and job cuts in the public sector (school teachers, doctors, etc).

In debt-ridden countries, the privatization of state-owned firms, which managed natural resources, water, electricity, transport and telecommunications, always has been carried out in the interest of rich countries’ multinationals. The contracts – signed against a background of corruption and political pressure – always have benefited these multinationals. At the same time, the populations under structural adjustment have grown poorer and poorer, their life expectancy has declined, their child mortality has risen and their literacy rate has dropped.

Most official reports indicate that the very indebted poor countries are poorer today than they were 20 years ago.

However, if we take into account the total capital flow and wealth transfer, African countries have more than repaid their debts to rich countries. Many of them have had to relinquish everything they owned and can no longer secure their future development.

A long overdue debt relief now seems to be deceiving. |